|

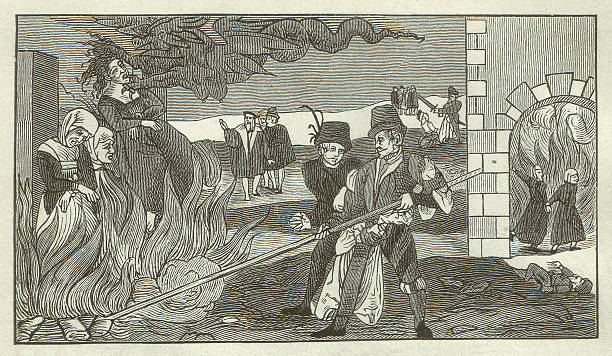

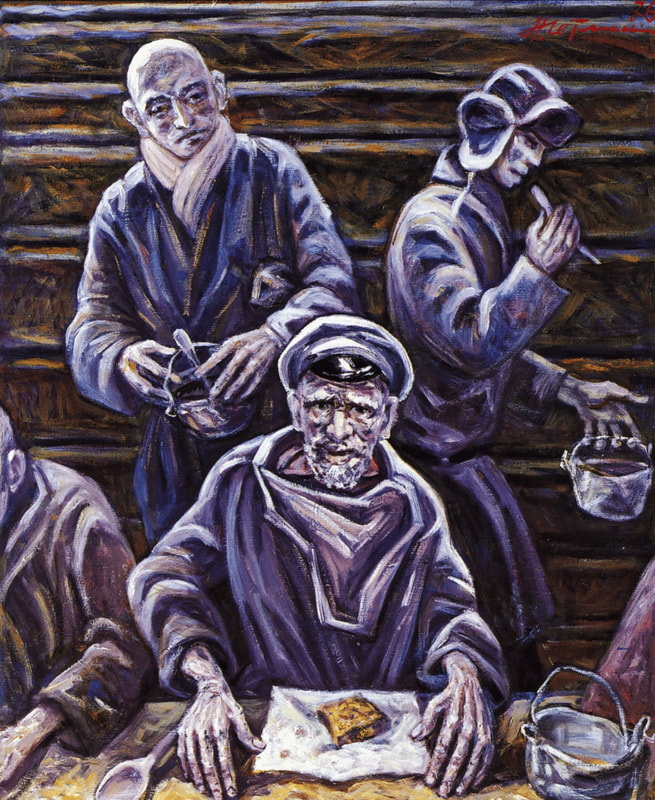

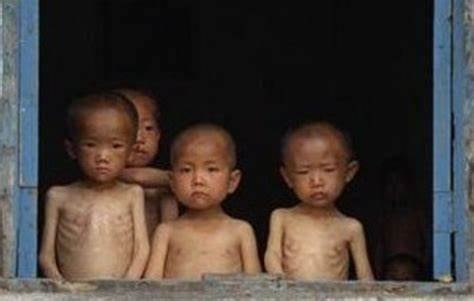

Any extremism generates pain for the vast majority for the illusionary benefit of the few. Anarchy Remember the French Revolution at the end of the eighteen century? Robespierre was a lawyer with good ideas and intentions. But the anarchy generated by the revolution transformed him into a monster where he ordered the killing of thousands of innocent people because they did not fit in his idea of what a “patriotic” individual is. He ended up like those he ordered killed. Religion intolerance When the church had the upper hand in the middle ages, they burned people on the stake for everything they considered not in line with their teachings. Or in the modern days, the genocide in Rwanda - initiated by Rwandan Catholic church. Or the one in Bosnia led by the Serbian Orthodox Church. And any other religion is doing the same when there is no other authority to stop them. Fascism Led to the execution of millions of Jews. Communism I know about communism. And what the system was capable of was shown from the very beginning. Do you remember Gulag? In Russia. Readers might read “One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich” by Alexander Solzhenitsyn https://www.amazon.com/One-Day-Life-Ivan-Denisovich/dp/0451228146 But it is equally bad in North Korea Readers may read about NK from a book inspired by a smuggled manuscript. “The Accusation” by Bandi (translator Deborah Smith) https://www.amazon.ca/Accusation-Bandi-ebook/dp/B095MDQ6V9 And it was pitiful in Romania. This book, “I must betray you,” describes the life of an informer in Communist Romania. https://www.amazon.com/Must-Betray-You-Ruta-Sepetys-ebook/dp/B09DS8BHR7 Or you may read real stories in my coming book, This Life. Keep Democracy! It is not perfect, as Churchill said: “Democracy is the worst form of government except all the others.” But still the best.

0 Comments

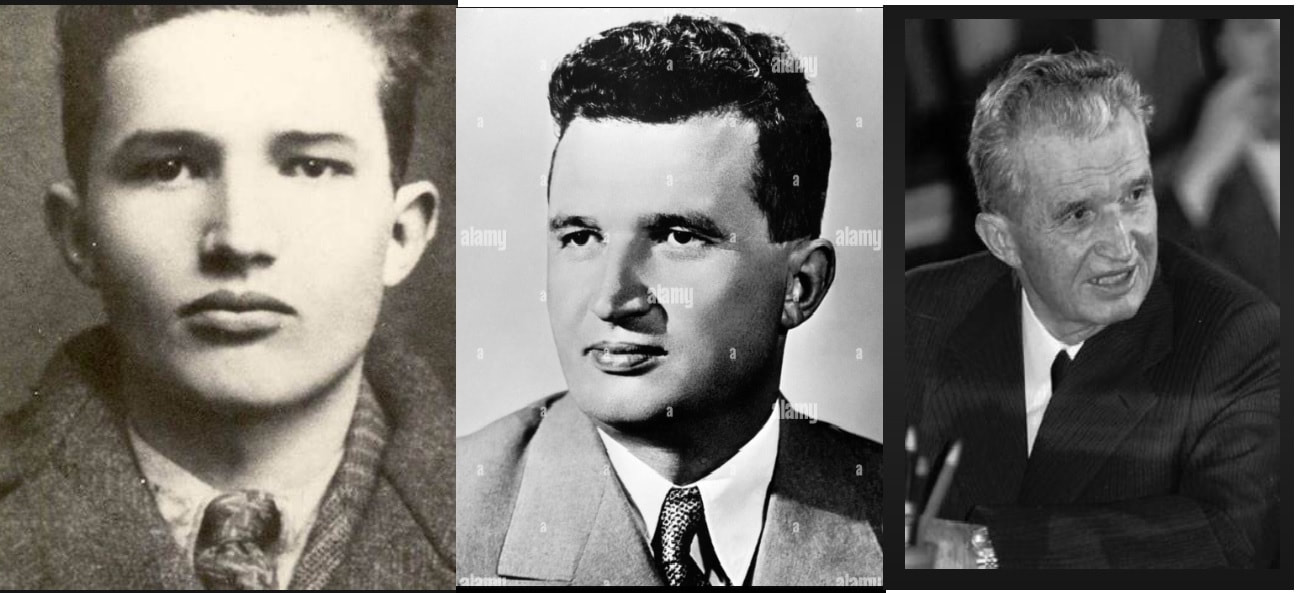

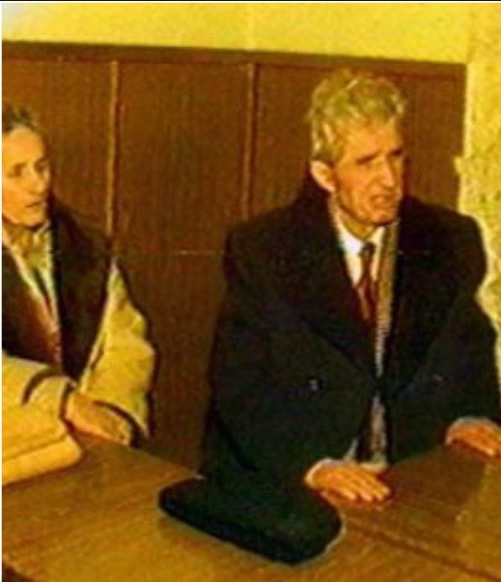

The end of an all-powerful dictator controlling the whole country with all means available, secret police, the army, and the high-ranking party members is mind-boggling. Most of my stories are during his reign. The story of his shocking death did not make it into my book since it is not family related, but it is worth telling. Few days before his tragic end… The meeting he organized in the Bucharest central plaza turned nasty when someone fired a firework that triggered the people to run (forcing the police positioned in a circle around the plaza) and shout anti-communist slogans. That moment the presidential couple, Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, scared, flew in a helicopter. About 80 kilometers north of Bucharest, the helicopter’s pilot, Vasile Malutan, had a radio conversation and told the president that they were identified and the helicopter could be shot down. Ceausescu ordered the helicopter to land. The presidential couple descended and, accompanied by the bodyguard, stopped a car. It was a doctor, Nicolae Deca, going home. Ceausescu told the doctor: “It was a coup, I organize resistance in Targoviste.” Targoviste was about 100 kilometers away. But in the first village, Deca said that his car had some mechanical problems. The bodyguard stopped another car, a man from that village, Nicolae Petrisor. After few stops, they reached a factory near Targoviste. Three police officers working there, Ion Enache, Constantin Paisie, and Andrei Osman, took them, intending to hide them in the police station in Targoviste. But in Targoviste the people were on the streets shouting slogans. Afraid, the group waited for the night near a forest, and then, under cover of the night, they reached the police station in Targoviste. As the official version of the event goes, “The following day, the Ceausescus were arrested by revolutionaries led by Ilie Stirbescu.” They were moved to a military unit near Targoviste. Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were executed three days after their arrival in that military unit near Targoviste. It was a mockery of a trial, on Christmas day, December 25, 1989. I saw that trial on TV, a few weeks later. Two lawyers were assigned to defend him. One of them did his duty and tried to defend the Ceausescus, but the other one, whatever he said, was more accusatory about the misfortune he brought over the country. The Romanian History site says this: “The process started at 13.20 and ended one hour later at 14.30. The sentence was deliberated in ten minutes, read at 14.40. Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were sentenced to death by shooting for ‘genocide, undermining state power, acts of diversion and undermining the national economy.’” The Ceausescus were dragged out near a wall. Nicolae did not fight, but Elena did. As I heard some rumors, the execution squad fired, but some soldiers on platforms further away, who were on duty to guard the unit, fired too. The judge who pronounced the sentence died by suicide a few months later. Ninety percent of the population was happy that Ceausescu disappeared from the Romanian political stage. Here is the end of the then-presidential couple as described in that History site: “The bodies of the two were wrapped in a sheet of a tent and boarded in one of the two helicopters, which took off around 15.00. They also had the members of the panel on board. The announcement about the trial and execution of the dictators appears in the media, only at 20.45. Overnight, the bodies of the Ceausescus were ‘forgotten’ on one of the sports fields in the Ghencea complex, being recovered the next day, and deposited at the morgue of the Military Hospital in Bucharest. Nicolae and Elena Ceuşescu were buried on December 30 - secretly - in Ghencea Cemetery.” Today that military unit where they were shot is a museum. The wall where the presidential couple was executed was renovated, but local authorities want to tear down the plaster, so visitors can see the bullets’ traces. Today, Ceausescu’s grave can be visited. There is a segment of the population regretting him.

One day, the city of Buzau hosted a soccer competition for the boys in the 10–13-year age group. The city’s team was in trouble. At half-time it was one-nothing for the visitors, and the Buzau team was lucky, it should have been more, but the post of the net saved them twice. They needed a soccer miracle to save day. And who else could come to the rescue but Ilie?

And, of course, Ilie knew that his help was needed. The second half had barely started when the majestic Ilie’s silhouette appeared over the grounds as he flew in circles above the soccer field. The visitors’ team felt uneasy, the strength displayed by the huge bird was not something to ignore. And the terrified visitor kids ran as fast as they could to the shelter offered by the cabin near the playground when Ilie launched like an arrow toward the field. But Ilie was smart enough to figure out that the commotion he saw below was too much. Instead of landing on the field he changed direction and sat on his preferred spot on the top of the oak tree. The moment of distraction was enough for a boy from Buzau to have a good shot and put the ball in the empty net. One-one. The referee called for all the boys from the two teams in the middle of the field. “The name of that vulture is Ilie. He is harmless, I would say, friendly.” “But we did not know!” protested the head coach of the visitor’s team. The referee was from Buzau, and was fair so far in the game. But that moment he was torn to pieces, and did not know what decision to take. Finally, he thought that he would rather lose his job than take away from Ilie his brave intervention. “One-one,” he shouted and stretched his hand toward the middle of the playground. Ilie did not move from his position the rest of the game. The visiting team was uneasy, and that gave the Buzau team an edge, they scored another goal. Two-one. The two teams gathered in the middle of the playground after the game. “We played eleven against twelve,” complained the head coach of the visitors. Some of his kids had tears in their eyes, they were a better team and lost. “And Buzau’s first goal was not fair!” continued the angry coach. The referee made a sign to the two coaches to approach. “I think we should cancel Buzau’s first goal and declare a tie.” The two coaches nodded. The referee turned to the waiting crowd and announced. “The fair score is one-one.” Everybody cheered. Buzau’s head coach went to the cabin and returned with an iron bar, then invited his assistant coach to hold it. The bar, in horizontal position, was soon graced by Ilie, who did not wait for any special invitation. A parade started, at its head the two coaches and Ilie in between them on the bar. The two teams followed, the kids from the opposing team stepping closer to the trio in the front, one by one taking turn, and touching bird’s silky wings. The news spread quickly, and crowds of people cheered the passing parade, Ilie watching them with modesty: Sure, no problem, not a big deal. Anytime. As years passed by, the people in the city became so used to seeing Ilie on the streets that some did not even notice him. Only when they had to make room for him to walk, or wagons and cars to stop and let him cross the street, was his presence remarked on. Some people were pissed off when they were in a hurry and had to wait for the mascot to pass. But Ilie soon sensed that, too, and changed his habits. He walked on the edge of the walkway, leaving room for pedestrians and vehicles for normal activities. He never went hungry because he knew how to ask for food. He stretched his neck, raising his head, and said loud and clear: “Ssssshaaasss.” And always someone jumped to the rescue. Ilie got older and preferred cooked meals. And he found where to get them. Of course, he found enough in Adam’s restaurant, but lately he enjoyed more what the cook in the train restaurant prepared. Almost daily he waited patiently in the station for the train from Cernauti to Bucharest to stop at Buzau. By then, the cook had his meal ready. The passengers, all at the train’s windows, watched the cook approach and place the meal at Ilie’s feet. “Ssssssshhhhhaaasss.” Ilie never forgot to thank. But the animal kingdom is strange. The animals feel when they have competition, and Ilie had his bitter enemies, the dogs and the crows. But no one was a match for him. He did not train to fight, but the king of the sky had instincts and force, the crows attacked him only when they were many. The people witnessed harassments, and they believed that one of the reasons Ilie walked more than flying was exactly that, to avoid the crows. As for the dogs, they ran, tails between legs, when Ilie approached. On the few occasions when there were bigger dogs approaching, in a pack, Ilie preferred, with a royal dignity, to fly. The saddest day of the century in Buzau was sometime in April 1942. A German soldier and his big dog entered the train station where Ilie waited patiently for the Cernauti-Bucharest train. Without any warning, the big dog attacked. Ilie did not have time to take off, and turned to fight. With his claws and beak, the vulture had the upper hand, but the dog was well trained. Still, you do not mess with the king of the sky. With a surprisingly fast move, unexpected from Ilie considering his age, he knocked the dog down with his beak, covering his head with blood. The soldier pulled his gun and killed Ilie with a single shot. Kids cried when they heard the news about Ilie’s tragic end. People were outraged. The commotion on the streets of Buzau was unprecedented. The crowd demanded the arrest and trial of the German soldier. The authorities had to dispense the police to control the mob heading for the German garrison. The day ended without any major incident. The crowd did not receive what they wanted, but local media were unforgiving. Here is what the local paper Vocea Buzaului (Buzau’s Voice) published on April 19, 1942, on page 4: “The eagle fell from a height at the feet of the vulgar man. […] I don’t know the killer, but I think he’s the lowest species ever created by nature, and that’s why I hate him, and that’s why I’m ashamed to be [of the same species] as him. He deserves to be punished for daring to kill trust and friendship.” The complete article was republished by other newspapers as well, including the well-known Universul (The Universe). Ilie was buried at Dumbrava cemetery, somewhere near the main alley. The authorities ordered a wooden sculpture of Ilie, still standing today in the Buzau train station. In case you missed the first part… http://www.eliademoldovan.com/blog/ilie-the-vulture-part1 I heard about Ilie the Vulture from a work colleague from Buzau, proud to tell us about the personality that dominated his city’s landscape for 18 years, from 1924 to 1942. The story did not make it into my coming soon memoir book, THIS LIFE, since it is not related to my family but is shocking.

Today, when the Internet is available for everybody to express their opinion and feelings, the people from Buzau wanted the whole world to know about their beloved friend; there are some articles about Ilie the Vulture, written by those who knew him. The key search words are “Vulturul Ilie” (Ilie the Vulture). I added two pictures on my site (www.eliademoldovan.com/ilieTheVulture.html), with Ilie on the streets of Buzau taken few months before his death, and his sculpture in the Buzau train station. * 1924, city of Buzau. Adam, the bartender, was sad. It was Friday and his restaurant was empty almost all day. Fridays used to be a busy day. Not anymore. A few more weeks like this and he would be bankrupt. He prepared more food than he could sell for the day, but he wanted to be fair with his customers, and not keep the food from one day to another. The food would end up in his neighbour’s coop; at least his pigs would be happy. Adam stepped in the little backyard of the restaurant. He was not tired, but still, he wanted to rest on the bench. When he opened the back door he froze. In the backyard was a huge vulture. “Go away!” he shouted, and waved his hands menacingly at the bird. “Ssssshhhasssss,” answered the bird, opening slightly his beak, then lowering his head. The bird is deadly tired, and in no mood for a fight. “What do you want?” “Ssssshhhasss.” Nick, Adam’s ten-year-old son, joined his father in the door’s frame. “Look at that, daddy.” “It’s a vulture, and I think it is tired and hungry.” “Give him food, daddy.” That was a good idea. Who knows? Maybe this is providence. “Bring the bag on the table, Nick.” Adam opened the bag with the food prepared for his neighbor’s pigs and took a piece of meat. He threw it at the vulture’s feet. The bird looked at it, and pondered for a while, then slowly lowered its head and took the meat, swallowing it in one shot. With another piece of meat, Adam approached, keeping it hanging from his hand. The vulture did not move. When the man was two meters away, the vulture stretched his neck, but did not touch the meat, it waited for Adam’s move. The man let the meat fall at his feet. The bird approached and took it, swallowing greedily. Nick joined. “Go back in the restaurant! It is dangerous!” shouted Adam. “Ssssshhhasss,” answered the bird, stepping backward. Nick clung to his father. “No, he is not dangerous. He is tired and hungry.” Adam smiled. “How come he fell from the sky in our backyard?” “Who is controlling the sky, daddy?” Adam smiled again. “The Saint Ilie.” “Let’s call him Ilie.” Nick tightened his grip on his father’s coat. The bird approached the fence and stopped, almost propped upright by it, he was indeed deadly tired. After few seconds Ilie closed his eyes. Sleeping time. Adam did not send Nick to the neighbor with the left overs. He had something else in mind. Next morning, the bird was still in the restaurant’s backyard. Adam approached, with the bag in his hand. “Look, Ilie, let’s make a deal.” “Sssshhhasss.” “I give you food, and you help me bring in clients to my restaurant.” “Ssssshhhasss.” Adam took out from the bag a piece of meat. Ilie did not move. Adam made two steps toward the gate exit to the street, then lost himself in the street, and came back after a few seconds. He repeated this movement several times. After a few minutes, Ilie understood and approached. Adam kept the gate open, waiting for the bird’s next move. This time Ilie understood more quickly and stepped into the street. The restaurant had a post in front of it, with a horizontal bar at the top on which a panel hung that read: Adam’s Restaurant / Food and Beverage / Best in town Adam put the food on the post. Some passers-by, afraid of the big bird, crossed the street, watching the show from the other side. It was a stalemate. Adam and Ilie both waited. Now or never! thought Adam, as he approached Ilie, taking the bird into his arms. “Ssssshhhhassss.” The crowd on the other side vocalized their astonishment. Adam put the bird on the horizontal bar. Ilie looked at the spectators with a definite sense of superiority before turning to the gift on the post, swallowing it. Nick showed up. “Ilie is our friend now.” “Yes,” confirmed his father. “Two or three more days without food and Ilie would have been dead.” “No.” “Yes, Nick. We saved our friend.” Adam lost no time and attached another panel under the existing one. Ilie the vulture is an honoured guest at Adam’s Restaurant, and he invites you to join him. Right after Adam attached the second panel, Ilie agreed. “Ssssshhhhasss.” Adam’s business flourished. And Ilie became the mascot. Walking among the tables, he received more food than he needed. He became stronger and stronger, but was always friendly. His life was not always easy, though. A newspaper accused Adam of taking advantage of his friend to promote his business. The story went like this. One day a lady came with her dog to the restaurant, early in the morning. Adam did not feed Ilie, since customers would do it for their amusement. The lady asked for a second plate for her dog, put the plate on the floor, and shared half her meal with her pet. Ilie recognized the food on the plate on the floor was for him and approached. The little dog jumped backward, scared, and barked furiously. Ilie was not bothered and swallowed the dog’s portion. The lady complained, hysterically pointing her finger at Ilie. Adam came, and when he understood what happened, took Ilie in his arms and threw him in the street, shouting for everybody in the restaurant and the street to hear: “There is no room in my restaurant for bad customers.” The lady got for free as much food as she wanted for herself and her dog. And the story made the news in the city. Ilie was furious. That kind of treatment was unacceptable. With his feelings hurt, he walked the street up and down in front of the restaurant, vocalizing at each turn, “Ssssshhhhhasss.” Then he decided that Adam needed a lesson. The market was only one hundred meters away. Ilie was more used to walking than flying, so he walked to the market, balancing like a duck, his feathers fluttering in the wind, voicing his displeasure. He was a celebrity in the city and well-recognized; some people made room for his angry marching while others laughed or whistled in disbelief. And Ilie was greeted with cheers at the market. He had his fill for the day. After a few days, Adam was worried that his clientele would thin, and he had to make peace with Ilie. He went one evening to the restaurant’s backyard. “Now look, Ilie. You sleep on my property, but you are all day long in the market.” “Ssssshhhhasss.” “Came back to the restaurant.” “Ssssshhhasss.” “I apologize for the treatment the other day,” said Adam, tears in his eyes. Ilie did not respond. “Come back to my restaurant, Ilie.” “Ssssshhhasss.” Ilie split his time between the restaurant and the market. Surprisingly, that was even better for Adam’s business. And for the market too! He was the city’s undisputed celebrity. A merchant heard about Ilie and travelled all the way from Braila to Buzau to see him with his own eyes. In Adam’s restaurant, the merchant saw Ilie patrolling between the tables, but avoiding to approach the new visitor. Ilie did not like the big cage near the stranger. “How much for the bird?” asked the merchant when Adam came by to take his order. “It is not for sale.” But Adam’s heart sunk. He wanted to expand and needed money. “Just name the price,” insisted the stranger. And Adam named a ridiculous price. “You got it!” said the man. The people in the city were enraged when they found the reason Ilie disappeared. Adam had threats and the clientele in his restaurant thinned by the day. But one evening, the whole city looked up to see Ilie flying high in the sky, returning to his friends. He landed in the backyard of Adam’s restaurant to the deafening cheers of the crowd who witnessed his touchdown. One day, from high up in the sky, Ilie say kids playing soccer. He descended, aiming for the ball. “Look up,” shouted one kid. They all raised their heads and saw Ilie landing like a plane on the soccer field. Ilie took the ball that was left unguarded by the astonished crowd. Aloft in the air once more, Ilie did not know what to do with the ball and dropped it back to the field. The kids cheered. Ilie landed on the horizontal frame of one of the nets. When the kids resumed playing, Ilie watched the game with great interest. He decided he should be part of it, and the children whooped with pleasure when he joined. The bird swooped after the ball each time it flew in the air and most of the time he caught it, dropping it back on the field. Ilie’s participation changed the long-held rules of the game. The children no longer cared who scored in net; rather, a point was awarded to the team who’s soaring ball was caught by the giant bird mid-air. Ilie showed up from time to time to the soccer field. Sometimes the kids wanted to play the real game, and Ilie felt it, he did not interfere, but instead rested on that tall oak tree near the playground. When the kids were bored with the game, mostly when one team was stronger than the other, Ilie sensed that moment, too, and it was his time, all the kids against Ilie. They began kicking the ball higher and further, wondering where Ilie’s boundaries lay. Was there a threshold he could not surpass? But Ilie’s skills grew, meeting each challenge the kids kicked for him. One day, the city of Buzau hosted a soccer competition for the boys in the 10–13-year age group. == Tomorrow my blog will finish the story == This is the first story, out of 21, from my book These Lives

The village was bewitched. The curse began a decade ago with the Second World War. Of course, the heaviest losses were among the youngsters. Those who returned were sick physically and mentally. The families whose dear ones never returned had to live with another penalty: their neighbors avoided them since they did not know what to say when the hard-hit families wanted to talk again about the missing ones. And for those who returned in a coffin, the coffins were heavier than in normal times, with too few hands to carry the weight. And after the war it was even worse. The newly installed communist regime sent signals that the villagers did not understand. “They would take from the rich and give to the poor,” was one rumour. Others said that “all the lands would be expropriated, rich or poor.” Some said that even the animals would go to the government. “I heard they will take our dogs too,” said one angry villager whispering to his neighbor and looking around to see if someone heard him. Others wondered if God had forgotten about them. The weather was worse than before. Too much sun or too much rain. The clouds were lower and more menacing. Others claimed that God was angry and spoke to them through thunder and lightning. In that summer of 1949 the lightning set on fire Rosca’s haystacks. When the villagers saw the fire and rushed to Rosca to let him know, he gritted his teeth and said, “Let them burn.” He did not want to give his hay to the communists; God decided for him. The mood was so bad that life began to give up; trees failed to blossom, the cows ceased to moo, and the dogs’ barks had less bite. The family was around the dinner table discussing the future under the new regime that they still did not know the extent of or the power it held. “We will lose our lands,” said grandma. My grandma, bunica, ruled the family with a soft touch. I remember her as small built and skinny, but her appearance was deceiving. She was the head of the household, constantly in motion, wise and understanding. Her unwavering belief in God gave her strength. And she was lucky with her kids. All six of them, four boys and two girls, were in good health and strong. My bunica died at 93. My mother, nineteen at the time, lost her temper. “What will happen with my tuition?” My mother was always calm. When angry, she would instead soften her voice and have tears in her eyes. But at that moment, her world was collapsing. She dreamt of town life, far from the hard labor in the field. In school, she studied with all her might to prove herself and encourage my grandma to spend the money for higher education. Our family’s prosperity had started with my grandma’s father who was a handy man. For his skills he received some land from the landlord. And the generations that followed knew how to administer it and they bought more and more and became one of the wealthiest families in the village. In three generations only, they had plenty of land and money. And now, the Communists wanted to appropriate it. “We need a lawyer,” grandma continued. “Maybe we can do something.” Our family knew a young man, the most active lawyer in town fighting on the farmers’ side against the government who had implemented a new law regarding agricultural lands. But despite lawyers, it was useless. All farmers lost their lands. So, my mother’s family lost their property, but my mother married the lawyer a year later. My father was eleven years her senior. They married in June 1950, the same month my mother was accepted to university. Their happiness lasted only a few months before my father landed in a political prison. By the time my mother started university, the Party had made school accessible for everybody, with no need for money. But my mother had to face some significant problems. The Communist regime decided to punish those who were considered rich before they took power. Those who were wealthy and those labeled as against the Party were barred from promotions and government positions. And that was for the lucky ones, since many were sent to prison for various reasons. And it did not stop there. Their children had to pay as well. The kids from rich or anti-communist families were purged from universities. Just like that. Agents interrogated all students. And they were very skilled. I do not know how the Party found the students they were looking for, what their methods were for tracking down their families’ economic histories. But of course, they knew. They always knew. And in those meeting rooms, they preyed upon the trembling voice, the perspiring brow, the clenching hands. I do not know all their techniques, but they were efficient. Most of the cases they built ended up as a successful purge. For each case, a file was created. Agents visited the “suspect’s” birthplace and asked questions. They had access to files about properties. And if the suspicions were proven true, the student was invited to leave university. For good. No one complained. My mother was in her second year at Cluj University when she was invited for the interview. It was 1952. She had two big problems: her family was probably on “the enemy of the people” list, but the biggest problem was her husband (my father) who was in prison for political reasons. The lousy omen that fell over her village ate my mother from inside. She lived in constant fear that any moment something would happen and oblige her to return and bear her share of the spell. Returning home did not mean working on the family’s farm, which existed no more, but working hard for a miserable salary. She prepared for the interview. She practiced the lies and her composure. My mother stayed in my great-uncle’s home in Cluj, my grandma’s brother from my father’s end. That very morning when she was due for the interview, grandma landed in Cluj. The three embraced warmly. The hard times brought all family members closer. Without any introduction, my grandma turned to my mother and said, “Don’t go for the interview.” My mother’s jaw dropped. “How do you know about the interview?” “Everybody knows what happens with families having someone in a political prison.” My mother swallowed hard. There was no way someone could have told her in that remote village about her daughter-in-law’s interview. “But who told you it is today?” “Maria, please believe me. If you go, it will be your last day in school.” I have to mention a few things about my father’s mother. She had eleven kids and had to navigate this world alone since my grandad died soon after her last child was born. And tragedies came one after the other. She lost three of them early on. But she managed to keep the family together with a strong will. She only gave advice on very few occasions and only in crucial moments. But I knew she had an extra sense. Her intense green eyes spoke more than her mouth. So, my grandma had that look, and the smile followed. My mother believed grandma. She was so scared that she would be kicked out of the university, and she had every reason to fear. About one week later, a security guard was waiting for her when she got out of the class. “Maria Moldovan?” he asked. My mother’s heart jumped into her neck. “Yes.” “The agent on duty wants to see you. At 11 AM, today.” That’s it, thought my mother. I’m done. She had one hour to prepare. She rushed home and donned her best dress, combed her blond hair and braided it back. The 22-year-old girl was about to face the most challenging exam of her life. The room she entered had two doors: one facing the street and the other facing the university. At the end of the interview, she would step through one of the two doors. The interviewer was already at the desk. “Good day,” said my mother. The interviewer nodded but did not invite her to sit. “What is your name?” “Maria Moldovan.” He smiled. But that smile made my mother freeze. The man looked at her intently, reading her mind. His face was rough, like an unfinished sculpture. Square face, strong jaw. His smile showed teeth good for breaking stones. His brown hair had a very short cut. And his eyes did not move in his head. All my mother prepared vanished. That guy is the Devil, she thought. And she cursed grandma, cursed the day for this unnerving man seated before her. Perhaps if she had simply gone to the first interview as requested, she would not now be facing the Devil. Without preliminaries, he asked: “Do you think you deserve the money the Party spends for you to attend university?” My mother swallowed hard. “Yes, my family and I are so happy with the caring way the Party is handling this. Without this kind of help, I would not be able to study; we are poor.” The man measured her from head to toe. She felt naked. And she cursed again because she dressed and carried her appearance so well. I know what he thinks. Only from good families does someone have such an appearance. I should have put some dirt on my dress and not washed my face! Dressing like this was stupid of me! This time the Devil darkened. “Are you married?” “Yes.” Then she continued in a hurry, “My husband is a lawyer and on a business trip in Brasov.” “What for?” But the tone of that Devil was clear. He did not believe a word from her. “The factory he is working for has a dispute with a provider.” “What factory?” My mother took a step back. The Devil’s eyes drilled through her. The question was a terrible blow. The agents could easily check whatever factory she named. There were few in Turda she could choose from and regardless, she had not anticipated the question. “The cement factory,” she said, faltering. But right after she spoke, she knew her fate was sealed. Her eyes grew wet. Without taking his eyes from her, the interrogator opened a drawer. Then he looked quickly inside and pulled out a folder with some papers in it. He put that folder on the desk. Then slammed it, his huge hand resting on top. His spread fingers covered its yellow surface entirely. My mother was trembling like a reed in the wind. The Devil raised the folder, waving it ominously. “It is all here. About your family and husband.” When he stopped waving it, she saw her name on the dossier. My mother started to cry. “All right,” said the Devil. “Now move, I am done with you.” And that man stretched his hand toward the door entering the university’s building! With all her bones shaking vigorously, my mother rushed through that door like the Devil chased her. That particular law forbidding students to enter university based on their family’s social status before communism lasted a few years. Somehow, on that day, my mother bypassed it, thanks to that… Angel in disguise who interrogated her. * My mother wanted to deliver the good news to my father as soon as possible. But the only way was the permitted once-a-year visit. It was only twenty or so days ahead. Her excitement was palpable. She was sure that my father would enjoy not only the news but the food she prepared. In the letter she received soon after my father’s arrest, it was stated that the maximum allowed food was 5 kilos per inmate. She changed the menu a few times. That letter, about a year prior, specified the week of October 20. She wondered why that date was chosen. It would make the trip difficult since it was during school. Was it planned to create additional hardships for the wives? It was brutal. There were many ladies with kids, and it was not easy to find a guardian or someone to accompany the kids to school and back. As for my mother, she had to miss one week from university. But it was worth it. My mother went to my grandma’s village to let her mother-in-law know about her plan. “I am happy that you’re going,” said grandma, “but I will not go.” “Why?” “Because if I go to see him, he will never come back home to see me.” I did not know that my grandma was superstitious, but obviously, I did not know everything about her. Or, maybe she felt something she could not express in words. “You see that apricot tree?” asked grandma. Everybody in the family knew about that one. My father planted it. He planted it as a teen before leaving for high school in town. It was in the front of the room’s window where my grandma spent most of the day when she was inside the house. And I am sure that gave her strength. “For two years, since Ioan is in prison,” grandma continued, “that tree did not bear fruits. But it did this year.” My mother turned, speechless, to see the tree. The wind started to blow with an unusual force and the dry branches were in full view. “Tell him,” Grandma said, “that I’ll wait for him this fall to cut the tree’s dry branches. It’s his tree and duty.” My grandma grabbed my mother’s hand. “The tree is sick.” But my mother was speechless, so my grandma pressed her hand harder. “For God’s sake, Maria, you know what I mean.” I don’t know what my mother thought at that moment, but I understand what grandma wanted to say. Watching that tree, she saw my father. An illness ate it from inside. As a kid, I remember that more and more dry branches had to be cut each year; life was running out of it. Scared beetles scattered from under the tree’s bark with each falling branch. The fewer and fewer remaining fertile branches lost their colors and freshness as time passed. And the tree’s sickness started with my father’s imprisonment. * My mother arrived on October 20th at the prison’s gate at about noon. Small groups of ladies were spread on the grass in the yard in front of the gates. They stopped talking and watched my mother approach. The gate did not have a bell or anything to alert the guards. And it was closed. She shouted: “I am here for the visit.” A guard came from the building toward her, stepping slowly, like he had all the time in the world. “Good day,” said my mother. “I came here for the yearly visit to see my husband.” “That was a month ago,” said the guard. “You missed it.” “How?” And my mother pulled out the letter she had. “Not that one,” said the guard. “You should have another one sent this summer.” My mother’s world collapsed. “I did not get that letter.” “I can do nothing about it,” said the man and he turned to leave. “At least take the food I brought. For inmate Moldovan.” The guard stopped for one second without turning. Then he continued his way inside. My mother watched the empty yard hopelessly through the closed gate. She was empty inside too. What kind of a trick was this? She’d prepared for a month for this visit, and in one minute, an inhumane guard brought her life crashing down. Again. Like when they had taken her husband away. Then she turned and saw the other ladies watching her carefully. She approached. One, as young as she, said, “There was no letter this summer. None of us got it.” Paying more attention, she saw about twenty ladies. I know there are hundreds of inmates, she thought. But maybe some wives and mothers had already left, and more would show up in the next few days. The letter she got a year ago said about one week of visits. An older lady started to cry. “The proof that there was no letter this summer is right there,” she said between hiccups. “The yard is empty. They did not let the prisoners out to see us. They knew we were coming.” “Maybe they are out for some work,” said my mother. She had heard about forced labor. The villagers around the prison saw them, and the word spread. “No,” said the young one. “Some of us have been here since three o’clock last night. No inmate came out.” “Why can we not see them?” asked my mother. The other ladies waited for the older one to speak. “They look like zombies, but the real reason is different.” She breathed deep and continued, “They do not want us to give them food.” “Why?” asked my mother, more and more alarmed. “Because they do experiments with them or want to get them sick. Some get only sweets, the others only fats.” My mother pirouetted few times, looking for clues. She saw the barbed wire fence and fixed her eyes on it. The young lady approached. “I know what you think, but that fence is not for our loved ones. Behind it are true criminals, thieves and murderers.” My mother was speechless. “They do not mix with each other, but the criminals receive much better treatment.” Then she put her hand on my mother’s shoulder. “I know someone in the village that offered me a room. You may stay with me if you want and try again tomorrow.” That night my mother found out why the lady’s brother was a political inmate. Romania had an extreme right organization, The Iron Guard. Those men were at the far right of the political spectrum, as bad as the Communists, who were at the far left. Bitter enemies, to the death. And The Iron Guard planned to overturn the regime. Her brother participated in a secret meeting out of curiosity; he was not a member. Secret police showed out of nowhere and arrested them all. Most were sent to “The Canal,” which was practically a death sentence. Her brother ended up in that prison camp with my father. The next day was the same, with no chance to talk to inmates or pass the food. The only difference was more ladies at the gate. This time the guardian showed up at about noon, and a higher-ranking police officer accompanied him. A captain. They opened the gates and stepped out. All the ladies approached and made a semi-circle around the two guards. The captain spoke. “I know what you say. That you did not get the letter this summer about the visit date change. I was not in charge of that task, and I cannot give you more details. Some may have gotten it. I see you number fewer than the inmates.” Some ladies started to shout. “They will come in the following days!” “Maybe not all inmates have a visitor!” “Tell us the truth!” “Why can’t we see them?” “At least take the food!” The captain waited calmly until it was silent again. “I am telling you what the commandment decided. There is no visit, and it is forbidden to pass anything to the inmates, food included.” The ladies vocalized their displeasure again, but much less than before. Some of them started to cry. “And there is one more order I have to let you know,” continued the captain. “You are not allowed to stay in front of the prison gates. In fifteen minutes, soldiers will come and drive away those of you who refuse to leave peacefully.” Then the two men turned their backs and entered the prison’s yard without locking the gates. A few minutes later, a squad of about thirty soldiers organized inside the prison yard. They had guns. Some ladies departed right away. But others waited. The squad did not intervene after fifteen minutes as the captain promised, but waited. Slowly, more and more ladies left. My mother was among the last, even if she knew right after the captain spoke that there was no hope of seeing my father. * During university my mother stayed in the house of my grandma’s brother, who had a house in Cluj. He did not have kids and treated my father as his own child. I was born in 1955, same year that my mother finished university, three years after my father returned from prison, where he served for two years and one month. My brother followed a little bit more than a year later. My mother was a biology teacher. But she delayed starting her career for four years to care for us. Her first job was in a village about 15 kilometers from the town. She had to choose from several settlements waiting for such a teacher. She was lucky. In one of those villages, the priest had been an inmate with my father in that political prison. The priest opened his arms wide, welcoming my mother into his house. She stayed there during the week and came home on Sundays. She was a teacher in that village for two years. Then, she found a position in town where she worked until retirement. After returning from prison, my father was banned from practicing as a bar lawyer. Instead, he was offered a lawyer position for the bread factory in town. The stories I heard about my father differed from the father I knew. He was very good at telling my brother and me stories from which we could learn wise things. But, obviously, the tragedies in his family, the hard times in the war, the regime change, his time in prison, and then the illness eating him from inside, changed him. His morals only crystalized, there was only right or wrong. Justice ruled mercy. We, his kids, either did things right or terribly wrong and faced his punishment. As I see today, most areas in our life are gray and need understanding. We had to pay the price because my father could no longer see those gray areas. His anger and frustration erupted sometimes. My mother knew how to handle those moments. Calmly, she ordered us something to do away from our father. We understood from her tone that we had to listen without arguing. And she stayed to absorb the anger. He was never violent toward her, but his mere presence during those times scared me to death. When he wanted to punish us physically, and mother was around, she stepped in between him and us. I am sure she heard harsh words in the evening for what she did. There were few times when she did not intervene. She knew that she would not be successful. We might have received the punishment, but she suffered more than we did, I am sure. I think my father faced his demons many times because I saw his face, tear stained. My father died when I was twenty. When I write this story, my mother is 92. Sometimes I raised the problem of my father’s cruel ways, but my mother always defended him. “He loved you,” she would say or, “He wanted you to grow right and wise, be someone of value.” I feared my father. But my mother was a saint. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed